Driving Mr Menzies

- DateWed, 27 Apr 2016

Jimmy Clements, a Wuradjuri man from down Gundagai way, walked all the way up to Canberra on hearing that the Duke and Duchess of York were set to open the new federal parliament.

First Nations readers are advised this article contains the names and images of deceased people.

It was May 1927, and Jimmy was pretty well known around the Limestone Plains, the natural amphitheatre on which the new federation's national capital had been imposed. Like other Aboriginal men whom the whitefellas regarded as amenable, harmless or both, he wore a copper breastplate around his neck bearing the name 'King Billy'. Supposedly symbolising the white man's respect for the blacks, the breastplate was little more than another testimony to the Indigenous man's subjugation to the invader.

With his bare feet, wild hair and his dusty, patched-up clobber, old Jimmy was a sight the police thought best kept from the royals. But when they shooed him away some of the locals protested. Jimmy won his way. He met George and Elizabeth. Then he shuffled off with his mate John Noble. For decades explorers, anthropologists, historians and newspaper writers claimed that the blacks of the Limestone Plains were extinct – killed by disease and grog, by settlers, police and soldiers. OnYong, the last chief of the local tribe, the Ngambri, in which Canberra's etymology is cradled, died in an inter-tribal clash in about 1850.

He was buried ceremonially in an upright sitting position. But soon afterwards the settlers dug him up, stole his cranium and fashioned it into an ashtray. I'm pretty sure I know who still has OnYong's skull. But that bloke never returns my calls. That's another story, really – and a digression from how blackfellas were viewed around the national capital when the parliament first opened. Which is to say they were pretty well thought of as non-existent –gone. Frederick Watson, in his A Brief History of Canberra (published in 1927 to coincide with the opening of the new interim Australian Parliament) wrote that 'virtually nothing' remained to indicate the 'former existence' of the original inhabitants. In Canberra, even ahead of elsewhere, they seemed to wish the disappearance complete.

Jimmy Clements died a few months after winning his wish to meet and welcome the royals to Canberra. They buried him on the furthest border of Queanbeyan Cemetery, for a black man could not, even less than 90 years ago, be put to rest in consecrated ground. And there he was forgotten.

Australia's new federated democracy was the toast of the world for its progressiveness on minimum wages and working conditions, women's suffrage and social security. But make no mistake, this was a country for the man of European extraction and Canberra was the capital intended to serve and strengthen White Australia.

And it was the town to which, just a few years later in 1930, a 24-year-old ex-soldier and talented cricketer, Alfred (Alf) George Stafford, arrived. A Gamilaroi and Darug man, born one of 12 children in Binnaway, New South Wales, he came to visit a friend briefly after being discharged from the Australian Army. He stayed forever after finding a job and subsequently opening a billiard parlour in Kingston, where he hosted the later world billiards champion, Horace Lindrum.

In 1937 he joined the Commonwealth Transport Department as one of its earliest 'transport officers' – early bureaucratese for public service drivers. Over 35 years until his retirement in 1972, Stafford drove countless politicians, among them opposition leaders and 11 prime ministers, including Joe Lyons, Earle Page, Arthur Fadden, John Curtin, Frank Forde, Billy Hughes, Arthur Calwell, Ben Chifley, Robert Menzies (during two stints as PM), Harold Holt, John McEwen, John Gorton, Billy McMahon and Gough Whitlam.

Stafford first drove Menzies – whom he always referred to as 'Sir Robert' – in 1939, during the brief, deeply flawed first prime ministership of the Liberal Party founder. And while this Aboriginal man from the bush was evidently fond of most of those he drove or otherwise worked for, it was to the waspish Menzies that Stafford, perhaps improbably to outsiders, became closest.

During Menzies' 16-year postwar tenure Stafford, the former first-grade cricketer of St George and the Australian Capital Territory, served as adviser for the selection of the Prime Minister's XI, beginning with the match against the West Indies in 1951. It was a duty for which Stafford, a left-handed batsman and leg-break bowler, was eminently qualified; in the 1920s he opened the batting for St George's first XI. At number three was Donald Bradman with whom, it seems, Stafford had a relationship that is perhaps best described as ambivalent.

The Menzies-Stafford relationship extended well beyond cricket, however. The two were lifelong friends and confidants. When Stafford's first wife Edith became ill with cancer in the early 1950s, Menzies – perhaps at the insistence of his wife, Dame Pattie, determined that driving the PM was keeping 'Alf' away from his increasingly onerous family responsibilities. So Menzies insisted that a job be fashioned for Stafford as a 'Cabinet officer'. This was effectively a position as a personal assistant to the prime minister, a messenger for ministers stuck in meetings and their butler, who'd make the tea and pour the drinks when Cabinet rose.

All the while, after the death of Edith in 1954, Stafford and his two youngest children, David and Diana, periodically lived in the Lodge. They did so at the insistence of the Menzies, so that Alf, with the help of one of the housekeepers, could better support his children as a sole parent. For the Menzies, who travelled on official business often, there was the added advantage that the Staffords could serve as caretakers at the Lodge while they were away. In 1956 Alf Stafford married another of the Menzies' housekeepers, Heather Nesbitt. The Menzies threw a wedding reception for the couple at the Lodge.

Journalists, it is said, write the first drafts of history. This may be true, notwithstanding the compromises that pre-eminent speed of delivery imposes on accuracy. Academic historians, meanwhile, warily draw clues from these first drafts then rake the archives for other, often more reliable, documentary 'fact'. Others, like Stafford, will incidentally find themselves in the front row – or the driver's seat – as history unfolds all around them.

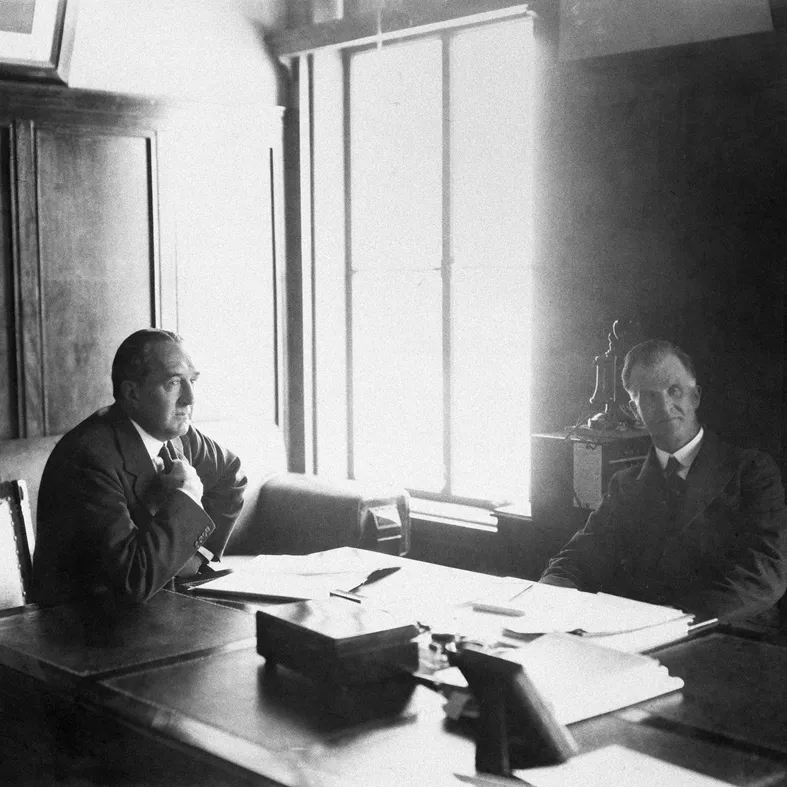

Stafford sat metres from Menzies, both in the car and in the prime minister's office, during a time of postwar stability, prosperity and social change. He was there as Menzies (with too much help from Labor's leader, Herb Evatt) fomented anti-communist hysteria, then as Australia began fighting the ultimately divisive Vietnam War. The growth of Australian industry and burgeoning middle-class satisfaction throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s coincided with the advent of the Indigenous rights movement that led to the successful 1967 referendum, which gave the federal parliament the power to make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Given that Stafford's service to prime ministers from Lyons to Whitlam points to a largely hitherto unrecognised Indigenous presence at the epicentre of Australian federal political life for a significant proportion of the twentieth century, it's reasonable to ponder whether he used his influence to try to further the lot of Indigenous Australians. But even among his own family Stafford exercised great discretion, so we may never know.

The Menzies' daughter, Heather Henderson – who recalls Alf well – has apparently told Stafford's children that it had not occurred to her that this confidant to her father was Indigenous.

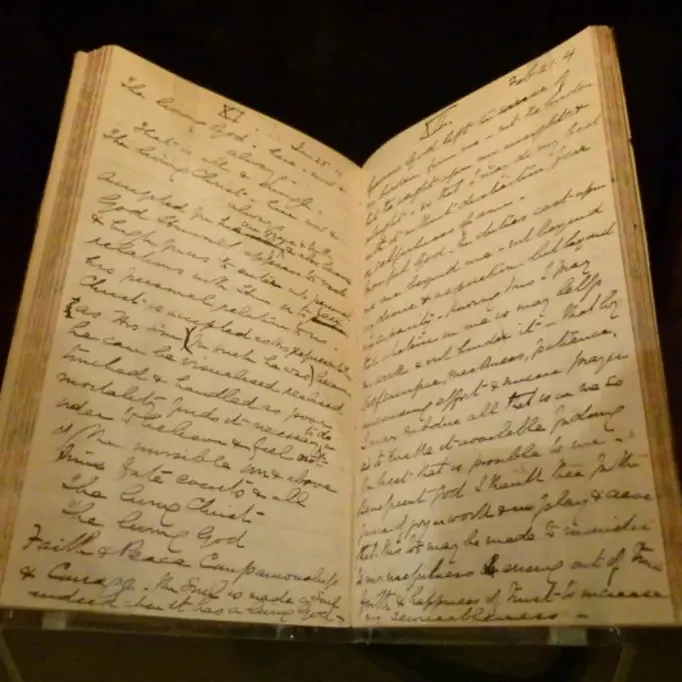

Stafford's extensive personal archive – including photographs of him with (and signed by) various prime ministers, personal and official correspondence, voice recordings and ephemera – is now held at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Stafford's granddaughter, Michelle Flynn, the custodian of this archive, gave the collection to the institute in 2014.

The institute's director of collections, Lyndall Osborne, said the collection demonstrated a strong historical Aboriginal presence at the highest level of federal politics. It is, she said, an 'important story for future generations to explore and learn about a man with Aboriginal heritage who was not only a close personal friend of a much loved former prime minister of Australia, Sir Robert Menzies, but also lived at the Lodge'.

This is certainly true. But besides a family tree tracing the Stafford lineage to early European convict and Indigenous antecedents, there is little evidence of any sort of preoccupation by Stafford with his own Indigenous heritage. Asked if Alf strongly identified with his Aboriginality, granddaughter Michelle Flynn says: 'No, not outwardly – just within the family… I suppose if someone had asked him he wouldn't have had a problem telling them. But I don't think that he advertised it.'

His daughter Diana Griffiths says he usually only broached his Indigenous heritage incidentally: 'I would have to say he never hid it. But we didn't talk about it and quite often we'd ask questions and… he'd say "Look at my nose, of course I am." And we just grew up thinking he was joking, I think. He was a very keen fisherman and he would say, "I don't really need to have a fishing licence because I'm an Aboriginal." This was his way of identifying with it culturally. Of course he looks Aboriginal – particularly as a young man in those early photographs. But we just didn't see it.'

Alf Stafford's youngest son David, meanwhile, says: 'In some ways it's almost odd that we were not conscious of dad's Aboriginality. I wasn't until after he'd died. Michelle says that he used to talk to her about it. But myself and my brother, to a large extent, weren't particularly conscious of it.' David says his father would make occasional comments about the Aboriginal side of his identity being displayed through his various pursuits, like gardening and fishing.

'And we'd just sort of think that he was joking about the fact that he was a mad gardener or he was out fishing and he'd keep little fish that were too small and he'd say "little fish are sweet" and we'd keep telling him they were also small. Down at the coast he'd be out on the breakwater with a screwdriver getting the oysters… he would just make that sort of comment from time to time and we just thought it was a throwaway.'

Menzies was busy running the country. So when the renowned Australian portrait painter (and mate of Menzies) Sir William Dargie came to Canberra to paint the prime minister in 1963, Menzies asked Stafford to sit in for him.

Dargie, an eight-time winner of the Archibald Prize for portraiture, painted Menzies at least four times. In two of the portraits Menzies wore the elaborate green velvet robes and heavy medallion of the Most Noble Order of the Thistle that the Queen had conferred on him in 1963. During 1963 and 1964 Dargie painted one of the portraits on commission to the London-based Clothworkers Company, where the painting still hangs. It is likely that this is the portrait for which Stafford sat in (or rather more accurately agreed to stand in) for Menzies. In one of several interviews for a Canberra community radio station towards the end of his life, Stafford – who was significantly shorter than Menzies – said:

'I stood in for Sir Robert when William Dargie did his painting… of his, his Order of the Thistle. And… Dargie painted the thing (medallion) around my chest… And I sat there for a couple of hours because he (Menzies) was so busy he couldn't make it so he made me do it, which I enjoyed – it was quite interesting. He painted in the face later.'

Stafford's daughter Diana observes: 'Sir Robert Menzies was a lot taller and a lot bigger than my dad. But they were both stout men and so you know the robes fitted on dad very nicely.'

This incident entices so many metaphors: of the Indigenous heart that beats, too often undetected and unacknowledged, at the core of national identity; of sovereignty's black core defying the white face; of the capacity for symbiosis between men with ostensibly little in common. At its simplest, the story behind this painting belies complex interpretation; it is simply a subordinate dutifully doing what a boss 'made me do'.

Regardless, the story was apparently sufficient to render John Howard – Australia's second-longest-serving prime minister, and a devotee of and political biographer of Menzies – momentarily speechless when it was recounted during a visit to the Stafford archive at AIATSIS. Howard visited the archive in the course of his research for his ABC television documentary about Menzies. A cricket tragic and Bradman aficionado, Howard interviewed Stafford's family for the documentary. He was, according to David Stafford, apparently captivated with a cricket bat that Alf won in a raffle to mark the first Prime Minister's XI match at Manuka Oval, Canberra, in 1951.

At each subsequent PM's XI match, Stafford – who would attend the matches with Menzies, having advised him on team selection – would ask the Australian and overseas international team members to sign the bat. It carries dozens of signatures in pen of greats from Hassett and Benaud to Colin Cowdrey. Alf ultimately bequeathed the bat to his grandson – David's son, Andrew – after he took five wickets in a schoolboy match. (Neither David not his elder brother ever made the century that would have earned them the famous bat, so it skipped a generation to Andrew.)

David Stafford recalls that when he showed Howard the bat with its fading signatures, 'I almost had to prise his fingers off it to get it back.' Of course, Howard would have noted the glaring omission of one signature – that of Bradman.

Bradman came out of retirement in 1962-63 to play for Menzies' XI. Despite great anticipation, he was dismissed for four by Brian Statham. It seems curious, given that Stafford and Bradman had known each other for almost four decades at the time of that match between the PM's XI and the Marylebone Cricket Club, that Bradman would not lend his signature to the bat.

Why not? David Stafford says: 'This cricket bat had the autographs of almost all the great legendary Australian players and English and South Africans and West Indians… But Bradman's signature is not on there. And we said to dad… "Why didn’t you get Bradman to sign it?" Dad said, "He wouldn’t sign it and I wouldn't ask him."'

Which begs a question that will, for a moment, be left to hang.

Alf Stafford, according to his son David, 'admired Bradman as a cricketer. He did not, I think, like Bradman very much as a person.' If this was the case, Stafford never publicly said as much when he was interviewed about Bradman on community radio. He was as characteristically generous to and discreet about Bradman as he was regarding most of the politicians for whom he worked, saying: 'I was lucky enough to be… in a few of the teams when Sir Donald Bradman was there. So I had quite a few times with Don. And I even played golf with him at Cronulla and tennis – he was really a brilliant all-round sportsman.'

This was as close as he came to being barbed about Bradman: 'I was an opening batsman and my boys, when they were about eight or ten, they reckoned I must've been better than Bradman because I went in before him.'

There was, however, one indiscreet recollection that Stafford shared with his family. The night before the PM's XI matches at Manuka, Menzies would host a dinner for his team at the Lodge. In 1954 the PM's team enjoyed what David Stafford said Alf recalled as 'a fairly rowdy sort of a night' at the Lodge that 'got a bit out of hand' when the captain, Lindsay Hassett, demonstrated his batting on the dining room table.

Heather Henderson was an adult by the time Alf and his children began staying at the Lodge. But she well remembers him and the special relationship he had with her father. 'Alf used to pour the drinks [after Cabinet meetings] and they did like to talk about cricket together,' she says. Recalling the circumstances under which the Staffords came to stay at the Lodge, she says: 'My mother would have insisted on it. They were very fond of Alf. He and dad had a very easy and close relationship that endured, from what I remember.'

Indeed, Alf's daughter Diana Griffiths says that as a child around the time of her mother's death, she considered Dame Pattie to be a 'surrogate mother'. 'Nothing was too much trouble for her. You could tell her your problems and tell her if someone was picking on you at school, and she would say, "Well, I'll fix that, darling."'

She says that she moved into the Lodge, where they lived in the staff quarters, with her father and David perhaps a month after her mother died: 'When things settled down a bit and when things started to get back to normal then dad was away a lot and travelling and so they took us under their wings. Then they went overseas and we stayed in the Lodge almost as a caretaker role. And so we had the prime minister's driver drive us to school and pick us up after school. We'd say, "Just stop at Kingston, Wally, and get us some ice cream". My friends were very impressed and the teachers were very impressed when C Star One [the Commonwealth car with the number plates reading 'C✩1'] used to pull up at school.'

'I have different memories. David says that we weren't there [at the Lodge] for as long as I remember being there. But we were there on and off. We'd sort of come and go. Dame Pattie would ring and say, "I want you here", and we'd have a month or so and off we'd go. I always had birthday parties and play dates. All of my friends came to the Lodge to play. Mr Menzies – I mean he used to come home from work and we'd be there at the door to meet him. Just like our dad coming home. And we'd go in and we'd sit in the little drawing room and he'd ask us all about our day and what we'd done at school and what we'd learnt. And he'd always read me a story.'

Menzies and his wife travelled extensively in the mid-1950s to places including England, the Netherlands, Greece, Germany, the Philippines, Malta and Japan. During their absence, Stafford and his two youngest children often stayed in the Lodge as de-facto caretakers. David Stafford says: 'After my mother had died, Dame Pattie had said it was no good dad driving Menzies – "Alf gets home too late for the kids," she told Sir Robert. "He needs a job at Parliament House." Menzies, effectively, I think, got the prime minister's department to create this job as a cabinet officer. All of which meant that dad got home five minutes earlier because he didn't leave… Parliament House until Menzies left and instead of driving Menzies to the Lodge and back down home in the Cadillac in those days… he'd just come straight home from Parliament House.'

'She [Dame Pattie] suggested that it might be helpful for dad to get settled if we moved into the Lodge because the housekeeper was still there. And they were going over to England by ship (away for six months)… which meant dad didn't have to cook meals – she was there for the children. And we knew her well. As kids we were often up at the Lodge with dad when he was driving Menzies. We were in and out of the kitchen. It was a different world. There was no big fences around the Lodge, there was a wire fence… all the back part was just like a farm-wire fence, a couple of strands of wire.'

Stafford's descendants emphasise just how discreet he was about his years of driving prime ministers and ministers, and of servicing the prosaic needs of Cabinet members (meals and drinks, messages and phone calls) when they met at Parliament House. While there were some MPs, prime ministers and ministers he may well have disliked, Stafford tended to be generous, even in private, to most of them. Stafford strongly indicated he did not like Billy Hughes (who changed parties five times during a long political career). In retirement, however, he never criticised Hughes, just mimicked his tinny, quavering voice instead. David Stafford says: 'He would impersonate his [Hughes'] voice sometimes. But… never really said anything derogatory about anyone that I can recall. He used to defend all of them to my brother and myself. John Gorton he used to defend when we used to say we're not too concerned about his relationship with [principal private secretary] Ainslie Gotto as to what he's doing to the country. And dad'd say "She's a lovely person." I think… he wasn’t terribly fussed about Billy McMahon though.'

As a driver to prime ministers and ministers, Alf Stafford had too many adventures to count. After drinking whisky with Hughes one wet night after the long, treacherous drive from Canberra, Stafford got bogged in the rose garden while reversing out of the then former PM's driveway in Sydney.

For a while Stafford drove the minister for the interior, the Western Australian MP Herbert 'Vic' Johnston. Johnston, also a keen fisherman, insisted Stafford drive him to the Gudgenby River, out past Tharwa from Canberra. Stafford would park the Commonwealth Buick on the narrow Glendale Crossing while Johnston fished out of the car window.

One wet night Menzies dispatched Stafford to collect the government whip, Jo Gullett, from his family property Lambrigg at Tharwa, ahead of a pending urgent parliamentary debate and vote. Stafford had his younger son in the car. David recalls the Cadillac reaching 100 miles per hour on the unmade, muddy Point Hutt Road. Alf Stafford, it is said, also held the record for the fastest driving time from Canberra to Melbourne of six-and-a-half hours (on today's highway, a good time might be seven hours, 45 minutes).

In one of those late-life radio interviews, Stafford recounted driving the Labor information minister, Arthur Calwell, through central west New South Wales on a freezing night in August 1944. Both were unaware that 1100 Japanese prisoners of war had just escaped from a prison in nearby Cowra. Four Australian soldiers and 231 Japanese died in the breakout: 'We were pulled up by a military convoy… they asked us if we saw any Japs on the road and we said no, and of course we didn't know what was going on. Just after that there was six little Japs walked down the road just behind us. I dare say if they'd wanted the car they could've knocked us off pretty easily.'

'Arthur Calwell then got out of the car – it was the middle of June… freezing… and he went up on the hills and it was just like a miniature war really, there was machine guns going and searchlights all around. And I had a good look at them and there was Japanese who'd hung themselves in trees with fencing wire and that sort of thing, others had knives and forks through their chests – they'd stabbed themselves in the heart…

And there was about eight of them the next morning who got under the railway bridge because the train was coming to Cowra and they all jumped out and committed suicide under the train. It was a very dramatic sort of a show… harakari (ritual suicide), yes… There was quite a few Australian soldiers killed, which we saw there. By accident we were there in the middle of it. I must say that Calwell did a mighty job. He got on the phone and got through to the papers in Sydney and asked them not to print anything on the show because we had prisoners of war in Japan.'

In Stafford's archive, Menzies emerges as his favourite boss. 'And also Chifley was a grand man. And Curtin. They were outstanding prime ministers. You could say those three,' he said when asked to name his favourite PMs. He spoke reverentially of a humble Chifley, the former locomotive engine driver who became Australia's wartime treasurer and, later, Australia's sixteenth prime minister. Chifley's humility was evidenced by his willingness, during the Second World War when charcoal burners were used on rural car trips instead of headlights, to get out of the car to help stoke and light the lamps. 'He said, "It reminds you of the old [train] engine, Alf."'

Alf Stafford retired shortly after the election of the Whitlam government in 1972, the same year he was awarded an Order of the British Empire. The week before Christmas in 1972, Whitlam wrote to Stafford: 'I understand you will be finishing up on Friday after twenty-two years of personal service in Parliament House to Prime Ministers.

What a record!

I have been a recipient of your services for only a brief week, but I have already come to appreciate your personal watchfulness over my needs. Your reputation is outstandingly high and I now understand by experience how well-merited it is.

You have presided over six Australian Prime Ministers! And not only that, you have ministered in your excellent way to a number of Prime Ministers and Heads of Government and, indeed, Heads of State from elsewhere. They would all support me in this appreciation of your services.'

Of course the great virtue of Stafford's long service, as both driver and (in the words of his son) as something of 'a glorified butler' to the Cabinet, was his discretion and loyalty to whichever prime minister he drove or served, and his effective invisibility to eyes beyond the old Parliament House or the driving pool.

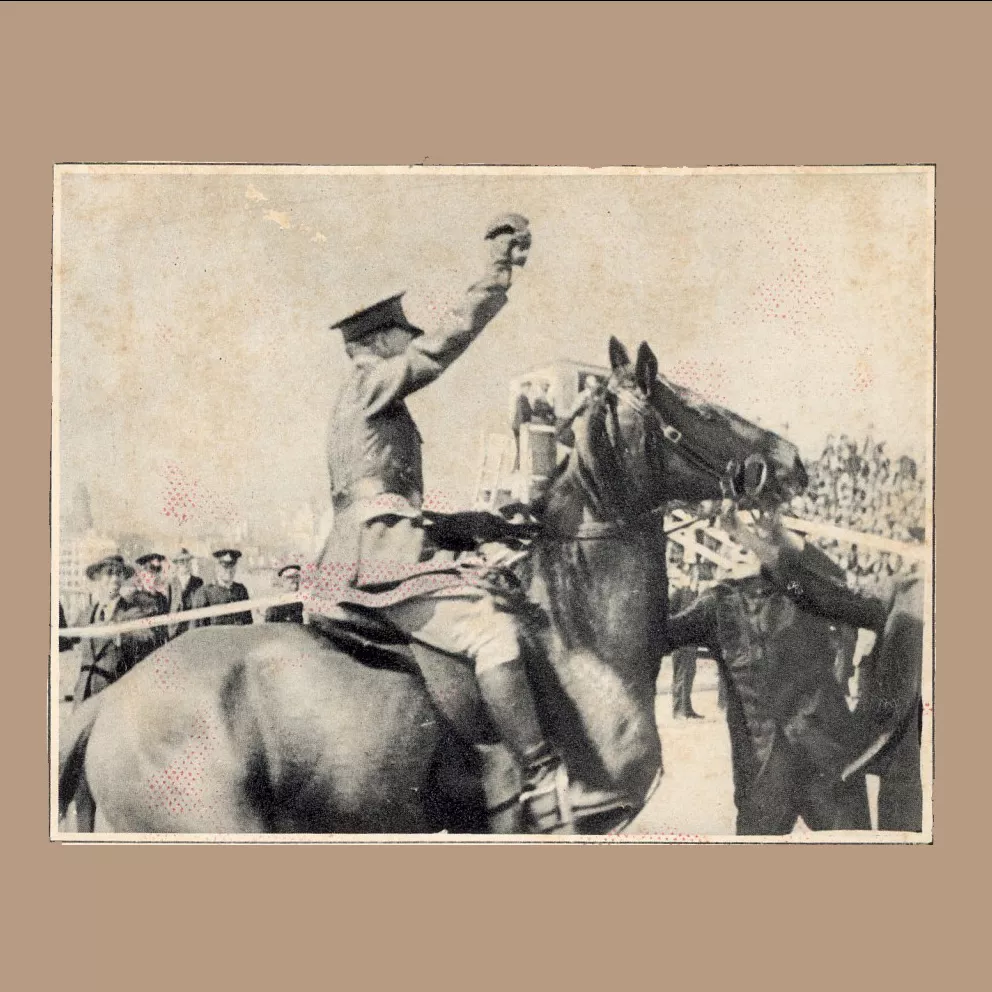

Well known in Canberra for captaining the ACT representative cricket side (he faced the first ball ever bowled at the PM's XI match venue, Manuka Oval, in 1930) and as a foundation member of the Canberra Racing Club (the Alf Stafford Guineas is raced in his name), officialdom cruelly overlooked him when the new Parliament House opened in 1988.

'With great regret, I must advise that we will not be able to meet your request that you receive an official invitation to the opening of the new Parliament House,' Jan McGuinness, an official of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, wrote to Stafford with cool efficiency. 'As several thousand persons have requested official invitations, you will appreciate that we have not been able to include all of them on the official guest list.'

Indeed, bureaucracy may have overlooked Alf Stafford on this occasion. But the prime ministers he served did not forget him, as evidenced by the correspondence in his archive. In October 1974, as Senate hostility, scandal and ministerial ineptitude plagued the Whitlam government, the ageing, increasingly frail Menzies wrote to his old confidant, the Indigenous man from Binnaway: 'I think we saw the best times, both in cricket and politics and living. Everything seems in turmoil at present and the cricketers even seem to be ordinary run of the mill, without any spark in them.'

'I trust you and your wife are well. You may have heard that I am unable to go far from home these days. My legs are letting me down. My wife is as spry as ever… We often think of you both, and the days in Canberra.'

Three of Alf Stafford's brothers served as light horsemen in – and returned from – the First World War at a time when Indigenous Australians were not permitted to join up. Another brother served in the Second World War. Alf, meanwhile, served briefly in the Australian Army when Indigenous Australians still faced obstacles in joining up (he said his skills as a cricketer made enlisting easy). It is clear that Alf Stafford identified with his Aboriginal heritage just as his granddaughter, Michelle, strongly does with hers – though more publicly than Alf did. She continues to research her background and plans a book on a remarkable heritage that illustrates the early colonial connections between convict settlers and First Australians. Of Alf's Aboriginal heritage Michelle says: 'Grandpa always told us about our Aboriginality but I became more interested not long before he died. Of course, I wish I had asked him a whole lot more about it all than I did. But we used to talk about it all of the time… and it immediately resonated and meant a lot to me in terms of who I am. When he died I got all of his papers which made it much easier to piece together – but I'm still on the journey, tracing new elements of our Indigenous history.'

For 35 years Alfred George Stafford was the obvious – but unspoken – Indigenous presence in the cars and offices of 11 prime ministers from Lyons to Whitlam. David Stafford says that when he and Diana reunited recently with Heather Henderson, they asked her if she or her father ever realised that Alf was an Aboriginal man. 'I mean, when we look back at photos of my father… you think, of course he was. But back then you didn't even give it a thought. And Menzies was no fool – he could probably work it out for himself. But Heather just said it never occurred to her: "Alf was just Alf."' But he was a lot more, too, you'd have to say.

Which leads us back to the question that hangs, awkwardly, over his relationship with Bradman and that refusal by 'The Don' to sign Alf Stafford's precious PM's XI bat. Nobody knows for certain, but David Stafford has given it quite some thought over the years: 'This is a bloke that he played first-grade cricket with at St George. Same team – better than Bradman because he was the opening batsman and Bradman was number three and even the kids know that – the best ones go in first, don't they? Of course they do. But he wouldn't ask him [to sign the bat].

Now we thought… having read a lot more about Bradman's personality and his view about signing things, knowing the value of his signature and being pretty reluctant to sign anything, you draw a conclusion that may or may not be entirely fair. The impression I certainly got was that [Alf] didn't particularly like him. Who knows where that may have come from? Dad in his younger days definitely looked quite Aboriginal. Is that a possibility? Who knows? This may be… the sort of reasons why he didn't sort of identify [as Aboriginal] particularly.

To me it's no particularly big deal. I grew up being just a normal kid and I'm not in any way perturbed by it – it's terrific. Also there's a bit of convict there too. You are who you are… Thinking about it later, you think, did Dad not make anything of this or not comment about this because it may have affected his life and achievements, where you get to, what you do in life? I mean he was an extremely good cricketer. But would he have been playing first-grade cricket for St George, captaining the ACT cricket team… if he identified as Aboriginal? Back in those days I mean those sorts of things did matter. Who knows? Would he have been driving the prime minister? Or would he have just become a bus driver?'

Alf Stafford died, aged 90, in 1996. Towards the end of his life, he remarked: 'In 29 years of working for the Cabinet I've seen and heard a lot. They used to say, "Prime ministers come and go but Alf Stafford goes on forever." I wish it were true.'

This essay was first published in Meanjin Quarterly (Autumn 2016), and reproduced here with permission.