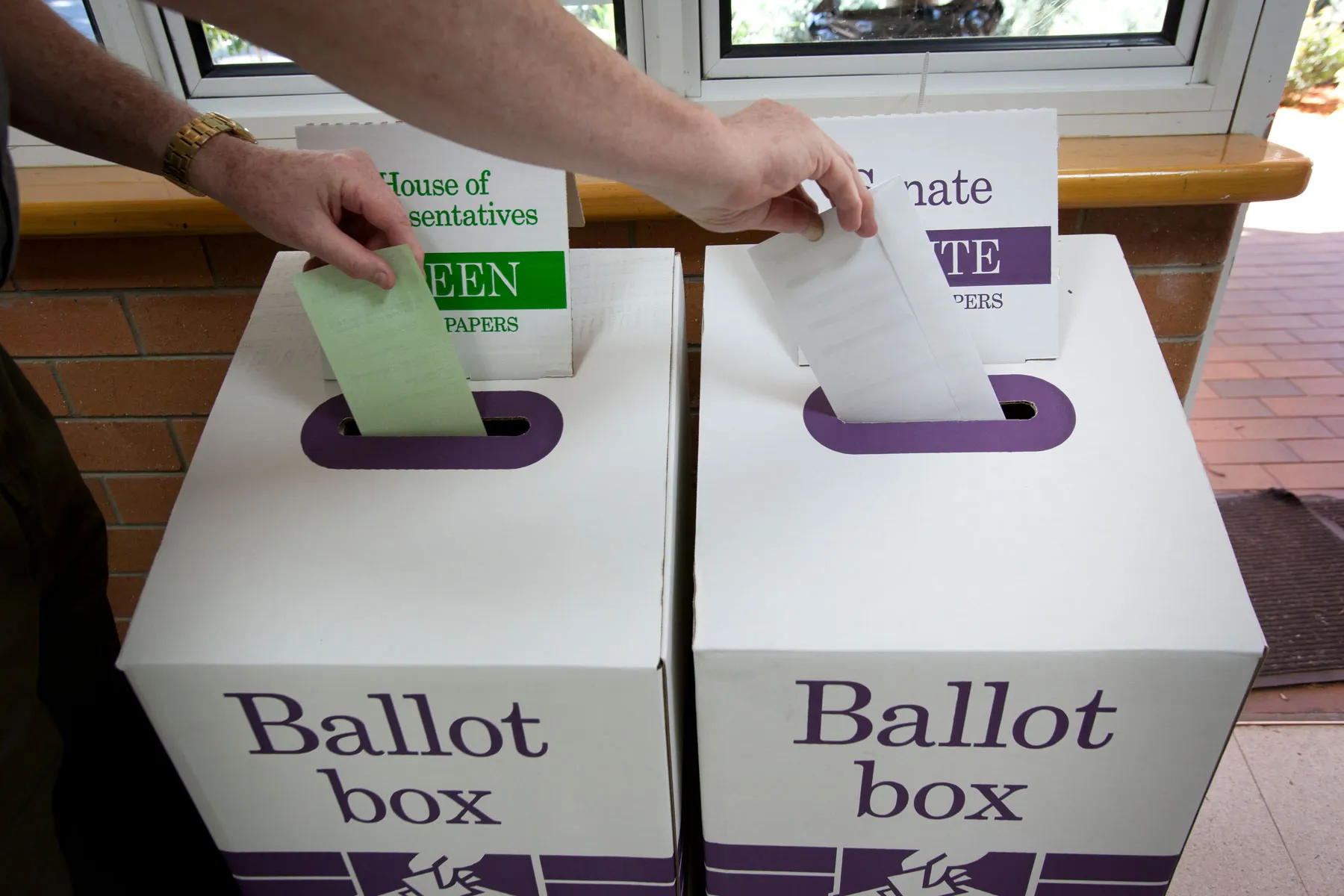

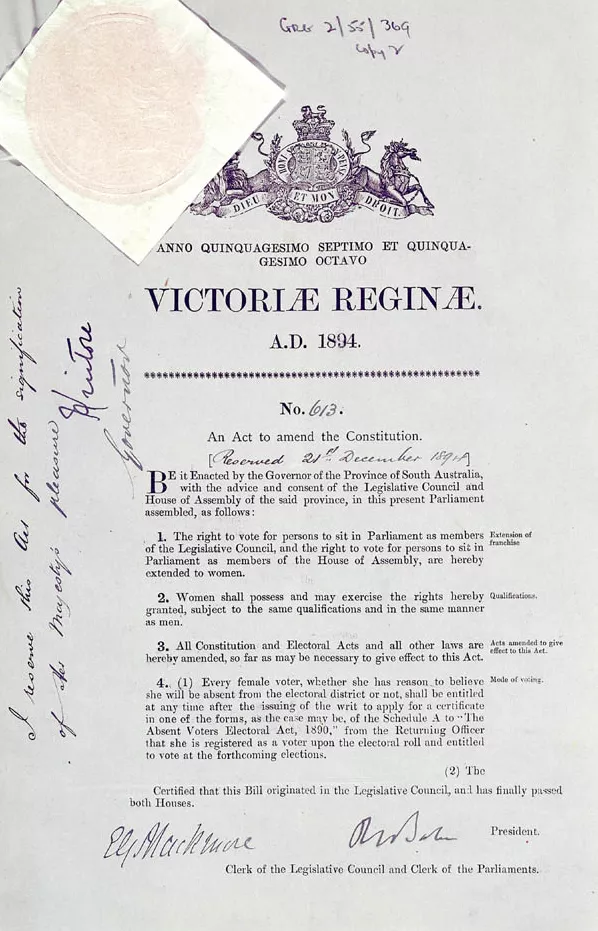

Democracy

How it works, why it matters and the power of your role in it.

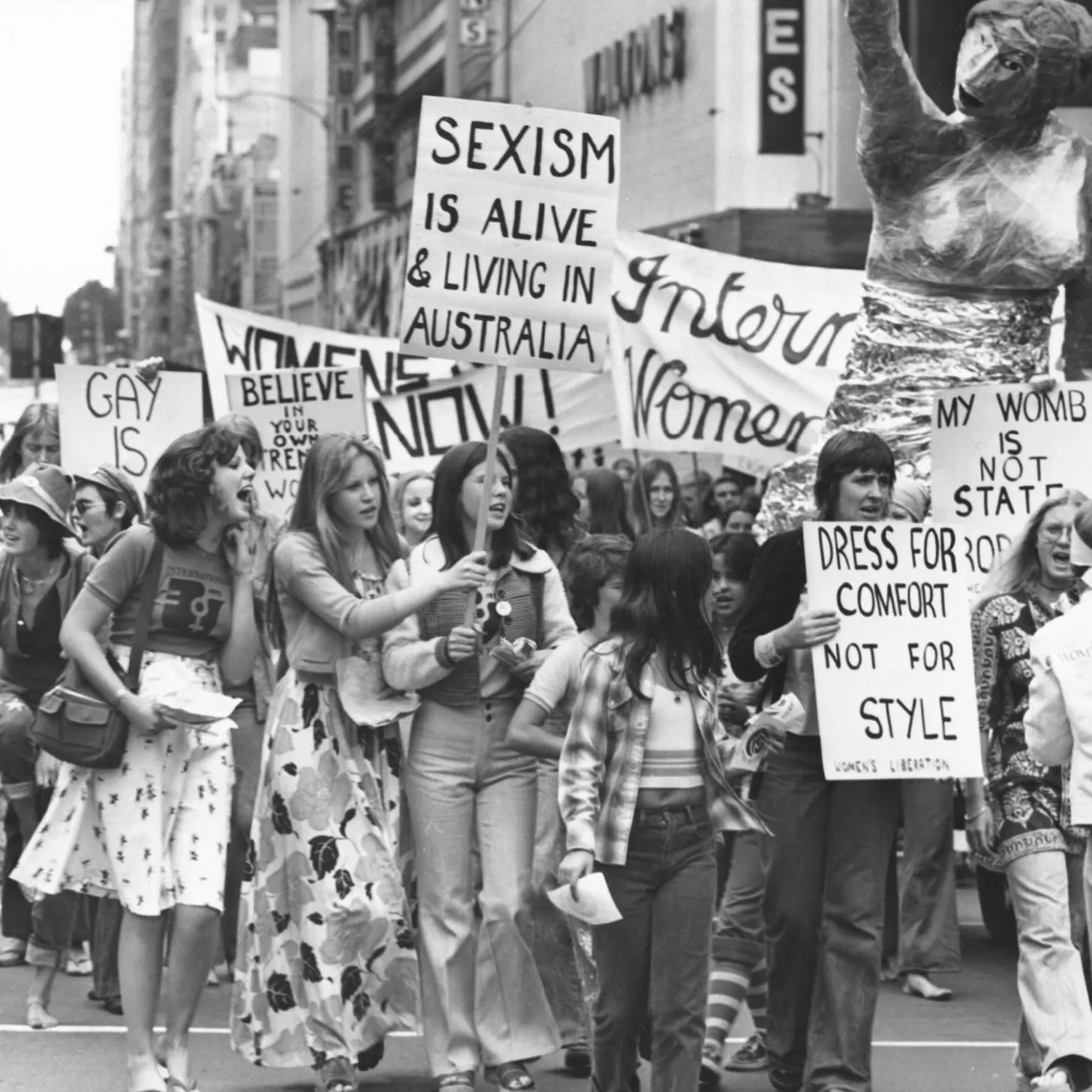

Democracy 101

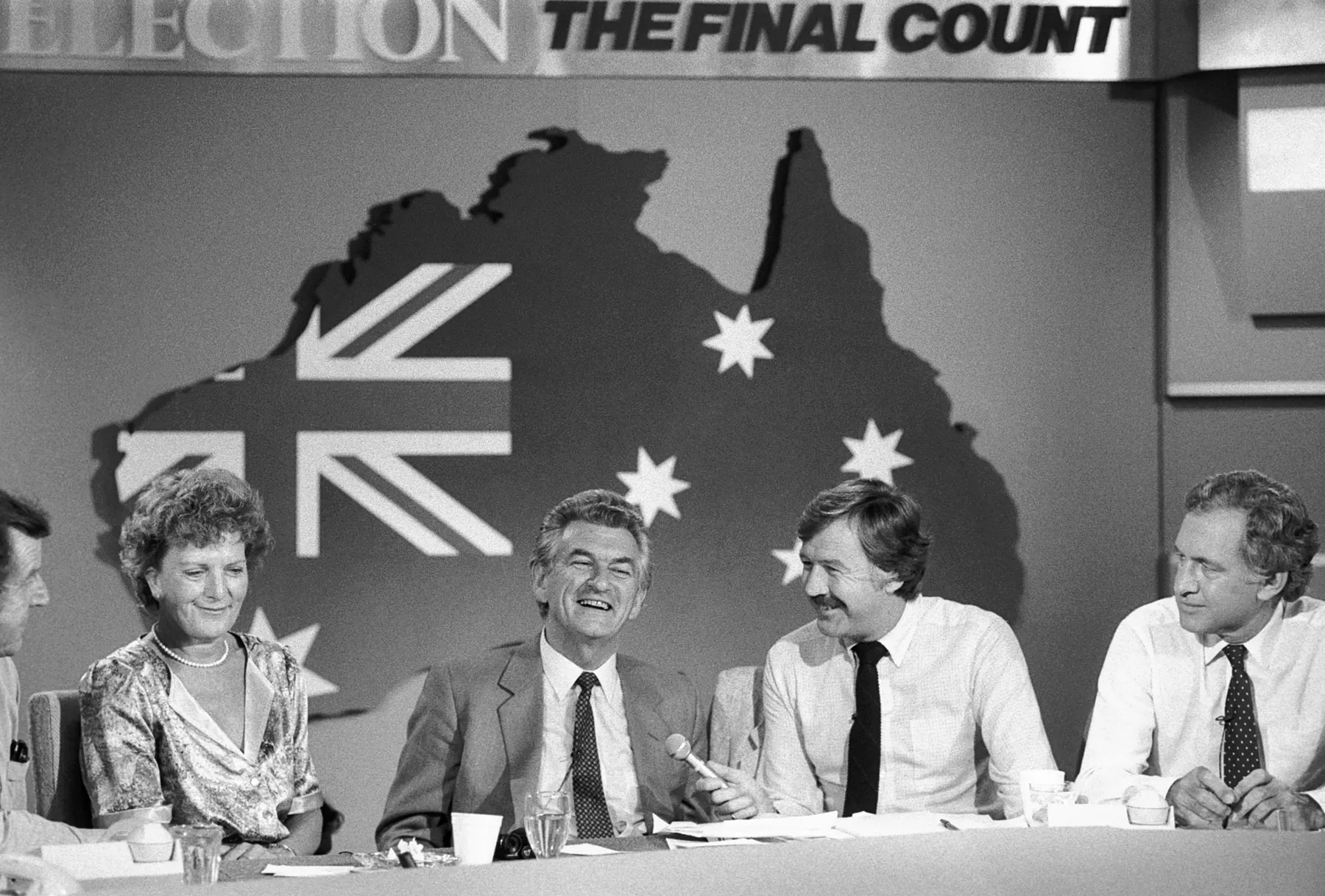

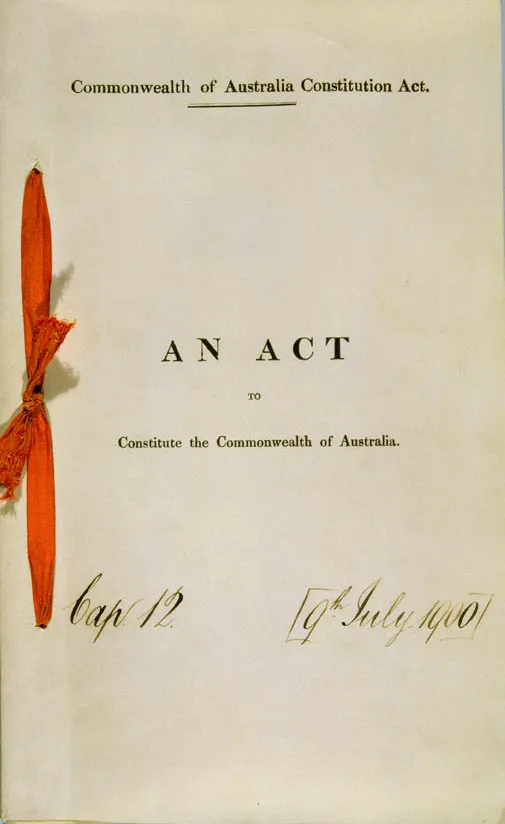

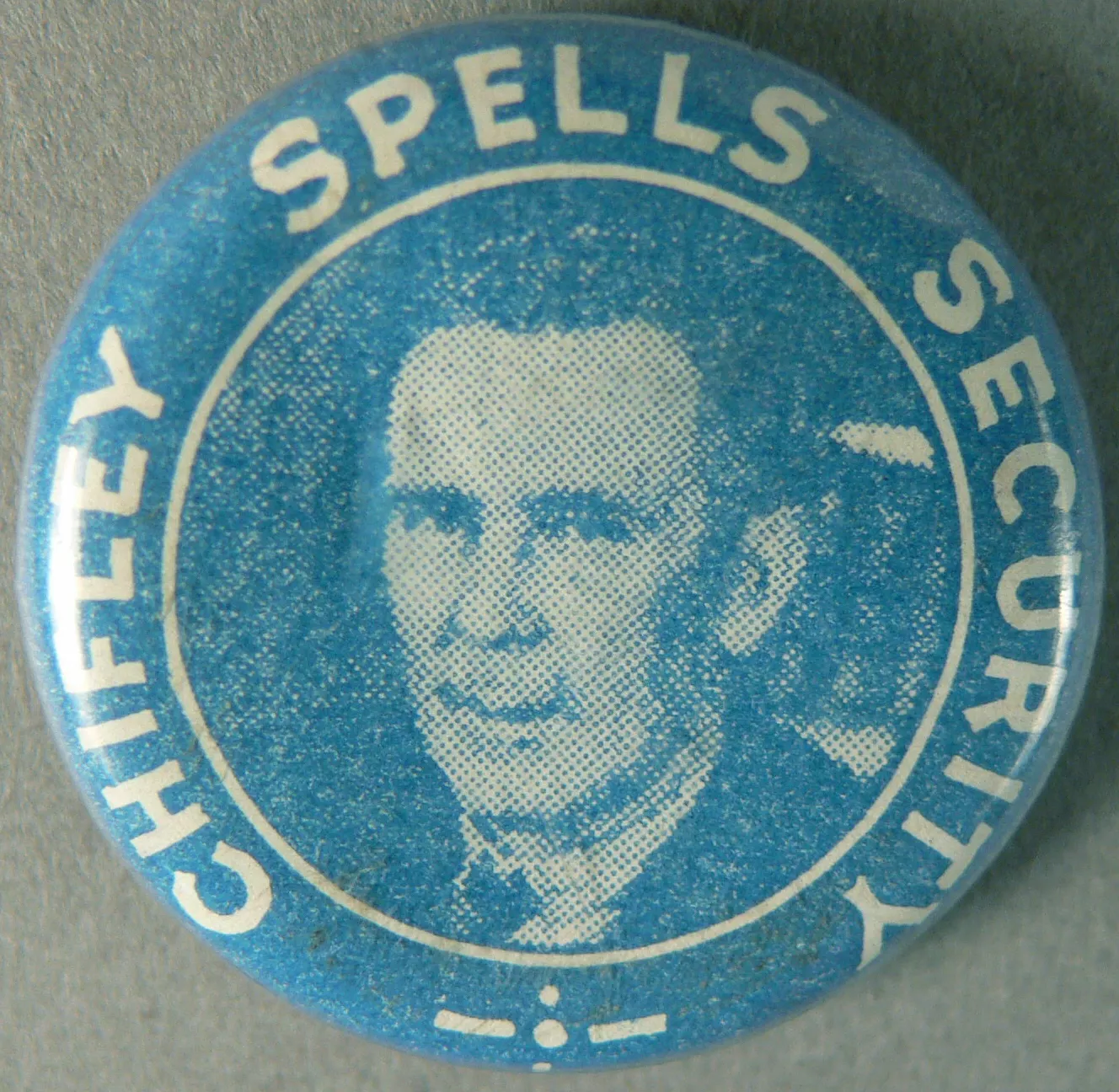

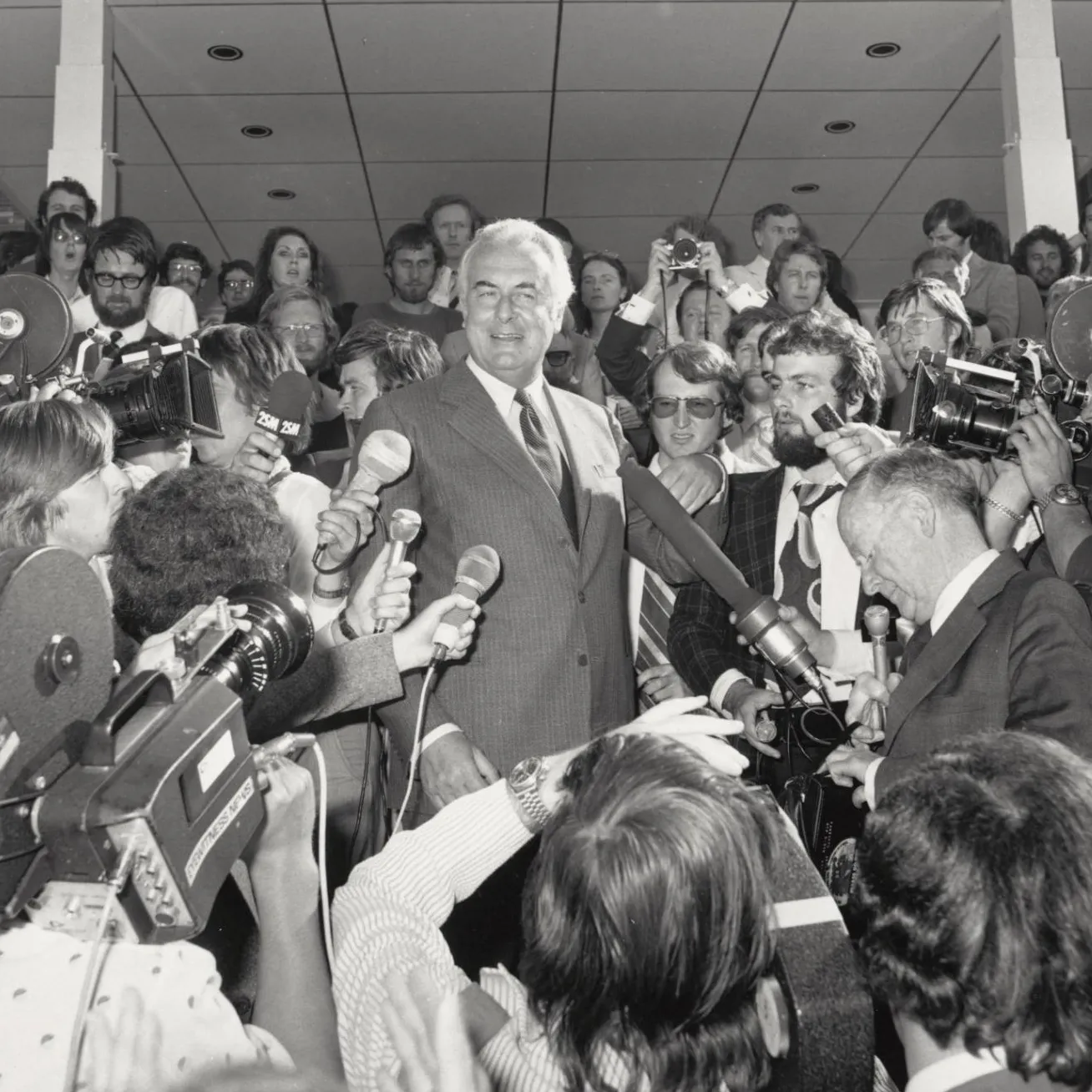

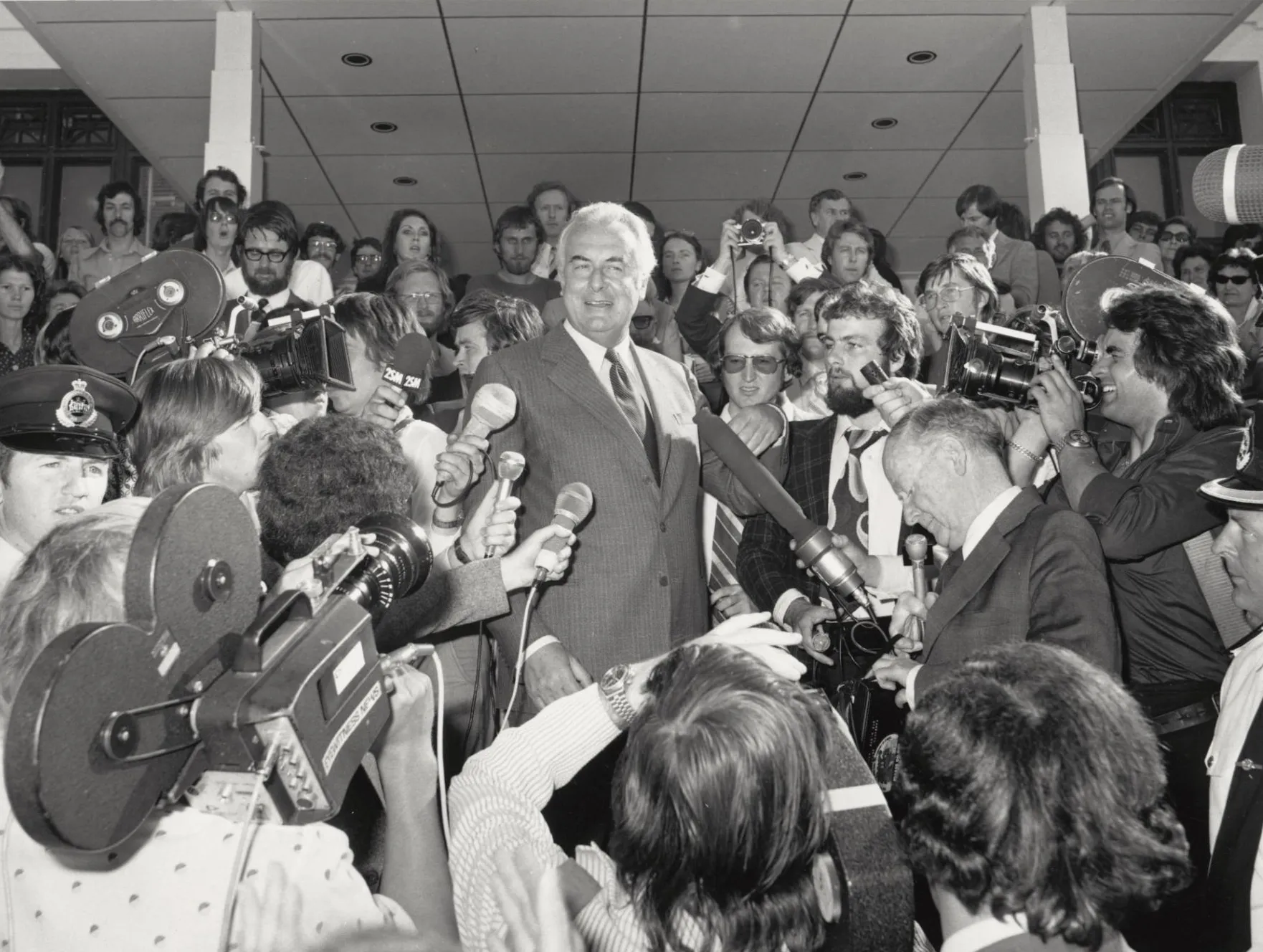

'WE'VE BEEN SACKED': THE 1975 WHITLAM GOVERNMENT DISMISSAL

For the first time in Australian history, the governor-general dismissed a prime minister and government. How did this constitutional crisis happen?

Learn more

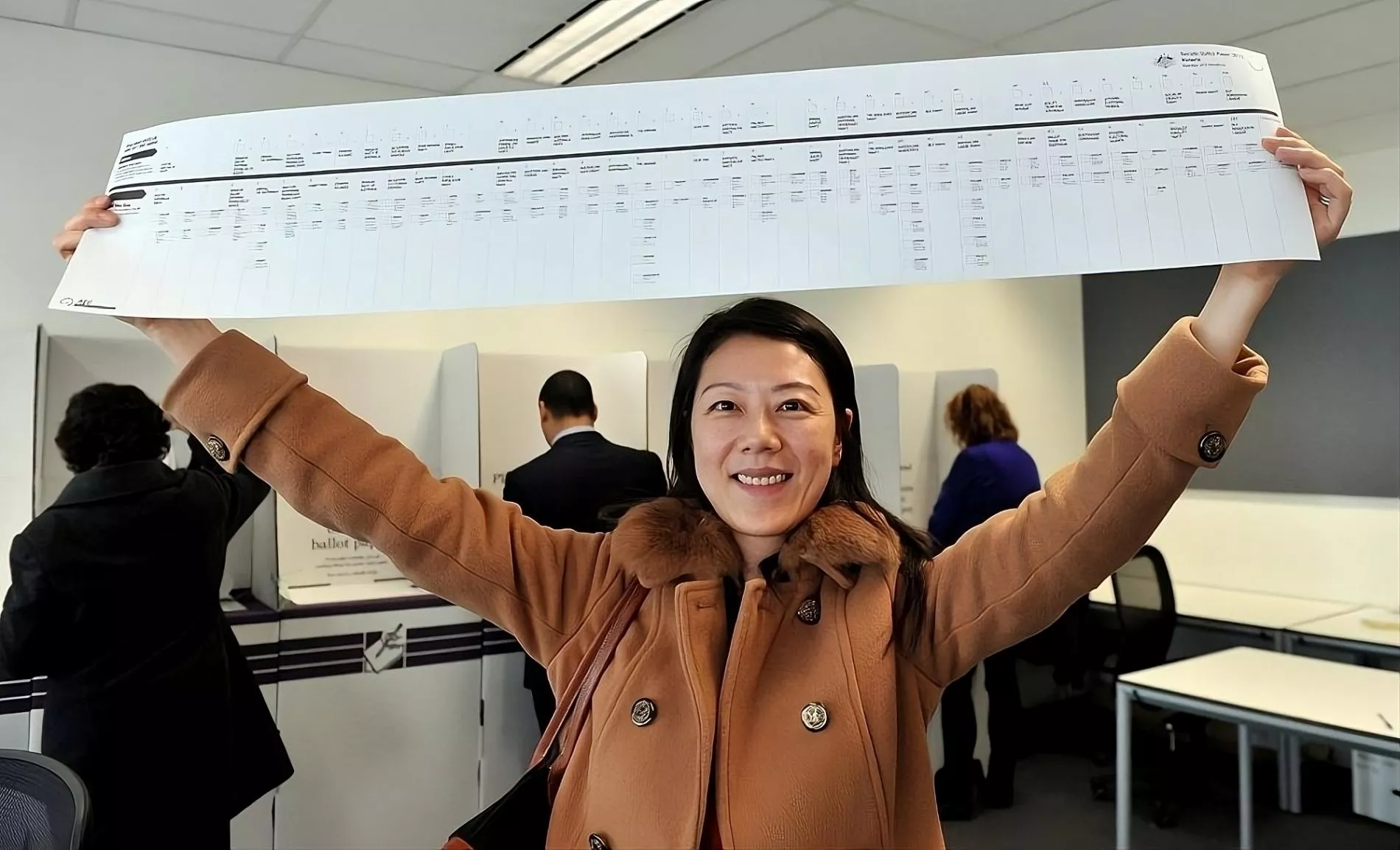

Election toolkit

Misinformation and democracy

MISINFORMATION EXPLAINED

Misinformation? Disinformation? What do these terms mean, why should you care, and what does it have to do with democracy?

Learn more