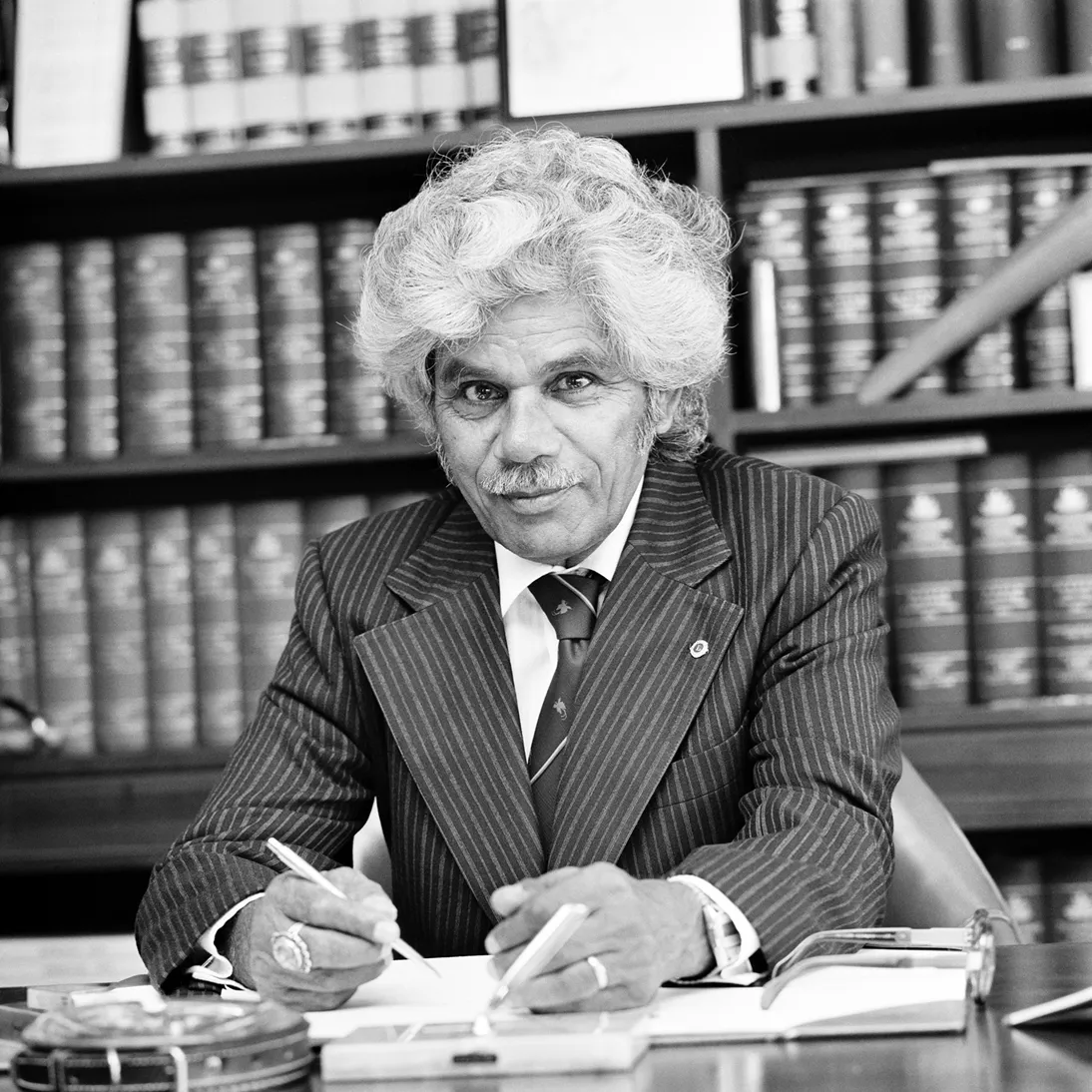

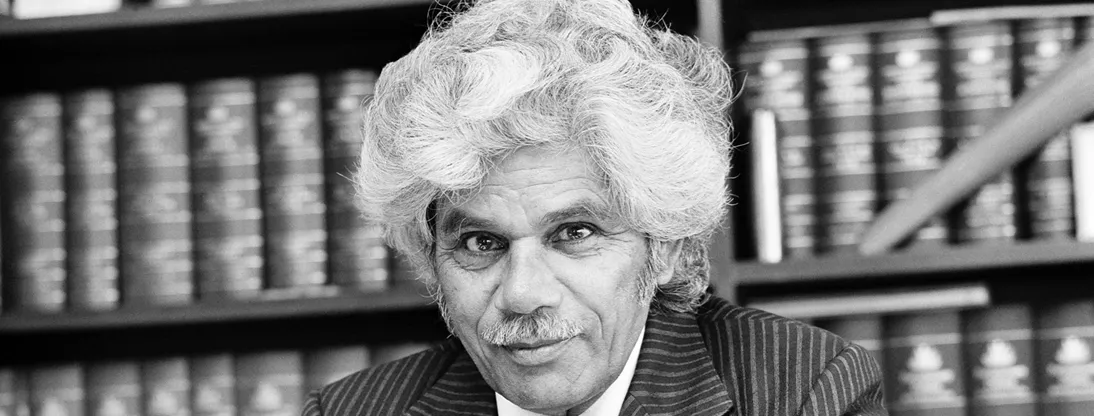

Celebrating Neville Bonner, the first Indigenous federal parliamentarian

- DateFri, 20 Aug 2021

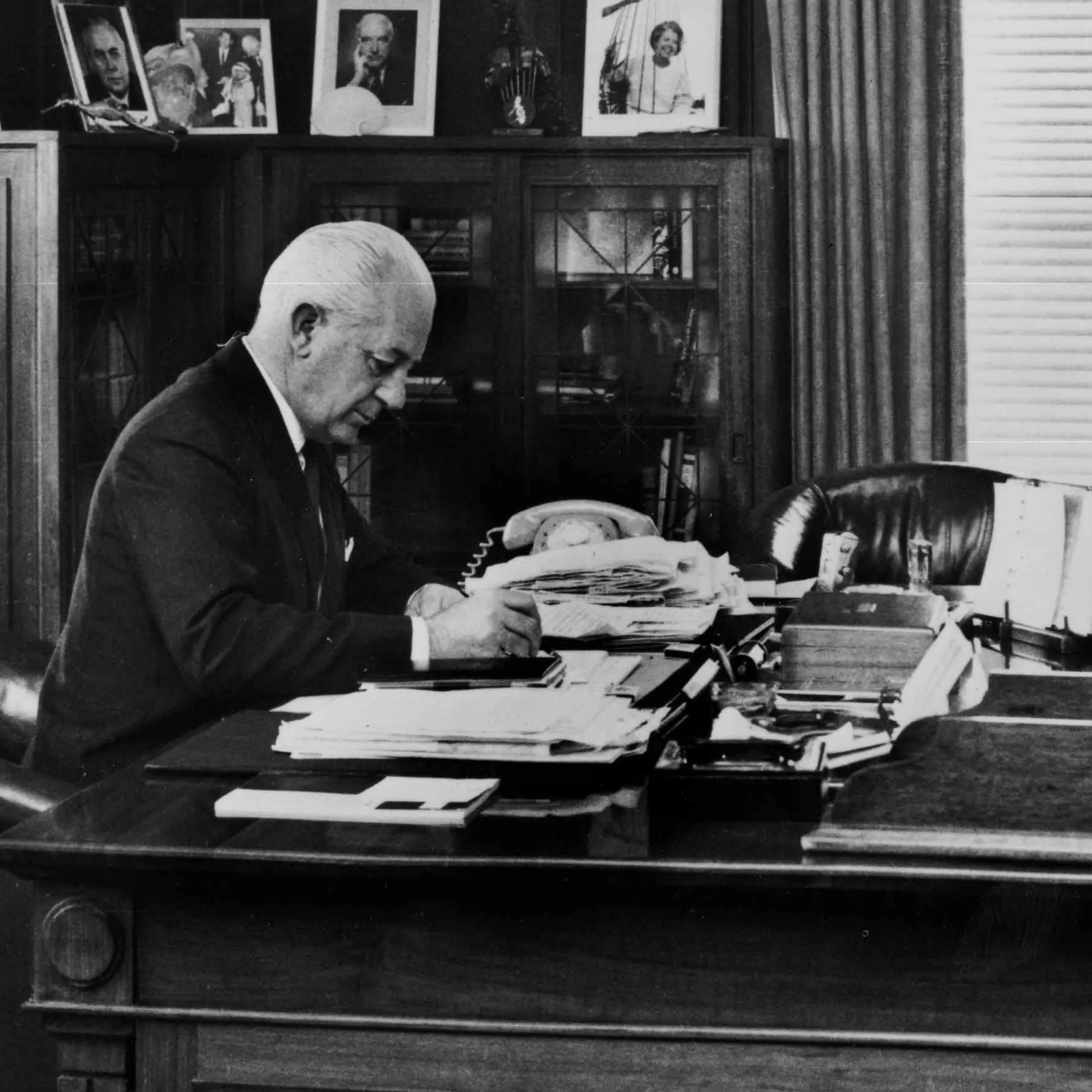

Jagera man Neville Bonner AO was sworn into the Federal Senate in August 1971, the first Indigenous federal parliamentarian in Australia.

First Nations readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

Neville Bonner’s career in federal politics began at Old Parliament House. A groundbreaking politician, he contributed to numerous Senate and Parliamentary Committees, advocated for Indigenous rights, and paved the way for future Indigenous Australians to enter politics. Today, MoAD is lucky enough to have numerous photographs and objects in our collection - many donated by Bonner’s family - that reveal something of Neville Bonner, his achievements and experiences. Learn more about these objects and the stories they tell:

The story of Neville Bonner

Neville Bonner’s self-proclaimed ‘burning desire to help my own people’ saw him campaigning for the rights of Indigenous Australians in the 1967 Referendum, forever changing the course of Australia’s political history.

After being sworn in as a Federal Senator on 17 August 1971, Bonner gave his first speech on 8 September 1971:

I shall play the role which my state of Queensland, my race, my background, my political beliefs, my knowledge of men and circumstances dictate … I realise the privilege and the double responsibility which has been bestowed upon me.

- Senator Neville Bonner

A bark painting by Elder Bill Congoo

This bark painting was created by Neville Bonner’s nephew Bill Congoo, an Aboriginal Elder and artist from Palm Island. The work traces Bonner’s life journey in four scenes: his birth, as he put it, ‘under a lone palm tree that still stands today’, on Ukerebagh Island, Tweed Heads, NSW; his time in Palm Island with his wife Mona and five sons; his move to Ipswich where he became involved in politics; and his parliamentary career.

Bark painting depicting Neville Bonner's life in four scenes.

1970s, Bill Congoo. MoAD Collection.

Liberal Party of Australia Life Member badge

Neville Bonner joined the Liberal Party in 1967, this Liberal Party of Australia Life Member badge was awarded to him by Prime Minister John Howard in 1998.

Neville Bonner's ‘Life Member of the Liberal Party’ badge.

MoAD Collection.

One People of Australia League (OPAL) badge

Neville Bonner’s commitment to the advancement of Indigenous peoples is reflected in his advocacy efforts with OPAL. Bonner joined the League in the 1960s and served as President from 1968 to 1974. He remained President even after entering the Federal Senate.

Bonner proudly wore this One People of Australia League (OPAL) badge in parliament.

MoAD Collection.

The Bonnerang boomerang

Bonner was a skilled boomerang thrower who learned the art of boomerang-making from his grandfather. In 1966, Bonner established ‘Bonnerang,’ a boomerang manufacturing business.

Bonner’s 'Bonnerang' boomerang. MoAD Collection.